“A metalhead and computer geek”

Seattle, 1999. Heart of the WTO protests, the dot-com bubble. Starbucks? (Ugh.) The Shizit, JP Anderson and Brian Shrader, lay somewhere in between.

Well actually, the Shizit begins just shy of that watershed in the final months of 1998. JP had been in a few bands prior, and was fresh out of an eastern-influenced, industrial rock band called NuMantra, they had a self-released album under their belt and song put on a compilation album highlighting bands from the NW United States. By late ’98, he was already writing and composing tracks which the Shizit would be known for. JP placed an ad for a guitarist in Seattle’s local alt paper, The Stranger. Think of it kind of like NYC’s Village Voice. Brian responded to the call, and the two were introduced in January of 1999. Brian was impressed with the tracks JP had, it was exactly what he wanted to play. He referred to himself as a “metalhead and computer geek,” a title humorously touted in just about every piece of journalism ever written about the band, and this bio will be NO EXCEPTION. Luckily, this was exactly what JP wanted to hear. By mid-99 they signed an agreement to be 50/50 partners and gave themselves the name “The Shizit” because, very simply, JP believed the band was the shit. Can’t argue with that logic, really.

A Quick Aside on the Tech

JP had a Roland XP-80 workstation keyboard which he used to compose and arrange all of the Shizit’s tracks aside from guitar and vocals, all of which were guerilla-recorded at their practice space into a Roland Virtual Studio. If the author had to speculate, they were likely using the VS-880 or 1680. These things were bleeding edge affordable recording stations at the time, and yet made completely trivial and obsolete by the computer workstation software that caught on just a few years later. If making electronic music seems difficult and ambitious today, it was ten times worse back then.

They used much of the same gear live, which you can catch glimpses of in the Herdcore video.

Brian’s guitar was tuned to drop-B and fed through a Digitech ValveFX rack processor. Digitech gave up on support for the product fairly quickly, so Brian went about developing software to create new effects (“patches”) in a graphical environment, releasing the software freely. You can still view the website he built showcasing the software.

“Are you ready for some fucking pain?”

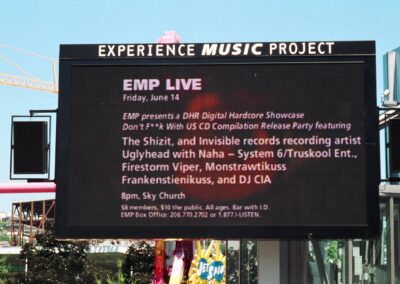

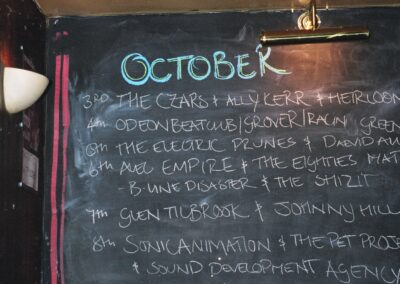

The Seattle music scene would not then, not now, not ever be kind to a band like the Shizit. Electronic rock, industrial metal, whatever-the-hell-you-want-to-call-it had very few home bases like Graceland, The Catwalk, and Fenix Underground. Sure, they played where they could, but indeed, they didn’t really play live all that much. The majority of photos you’ll see still floating around the internet are from a handful of shows: mostly their showcase at the EMP Sky Church and their UK tour with Alec Empire.

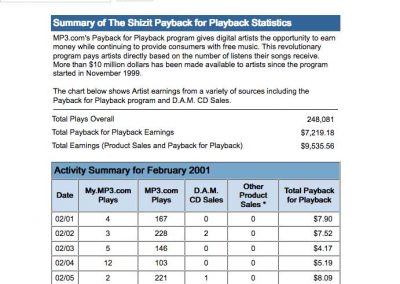

To gain an audience that actually connected with their music, they’d have to embrace the nascent tech emerging at the same time the band was. At Brian’s urging, the band put up a website, and gave away songs for free there and on mp3.com. Major labels at the time were charging out the nose for CDs. They thought they had a stranglehold on media and could keep it forever. In 2018, we know exactly how deep the bottom was for the recording industry as they continually tried to step in the way and use the law to halt progress. In 1999, however, the band was rather brave. At best, the band stood to gain a few more listeners; at worst, they’ve devalued their music to nothing.

Like any band, The Shizit’s first tracks were raw. Some songs were personal, some were this sort of high-concept adolescent cyberpunk anthem. The recording was lo-fi. In this author’s opinion, the best was yet to come. It didn’t matter, their sound didn’t have much of a parallel, and it clicked with the audience on mp3.com. They were topping the charts, not just of their genre, the entire site. It’s something we take as a given now, but mp3.com had the novel concept to compensate their top artists with a share of their ad revenue. Probably not enough to quit their jobs, but the band was earning enough to know they were doing something right.

“We are starving and bleeding before we unite on anything”

The music starts speaking for itself here. The 1999 debut EP “Evil Inside” gave way to the 2000 EP “Script Kiddie”, featuring polished re-recordings of some favorite tracks and demos of their debut album to come. The sound and the lyrics JP was bringing to practices began to evolve and mature. The songs became about what was discussed during the band’s practices, namely politics. Who could blame them? They were present at the WTO protests in 1999, they saw pigs bashing in heads and stopping people from being able to speak their mind. Their music would be about what they saw and felt at that time. They wanted to radicalize.

Their 2001 debut LP, then, is extremely appropriate, titled “Soundtrack For The Revolution” (stylistically abbreviated on the front cover to so.f.te.r, or just softer). The album was dedicated to the memory of Carlo Giuliani, gunned down by the state during protests around the G8 summit in 2001. The back cover featured a stylized edit of the “RESISTANCE” poster used by the IRA. The whole package was unapologetic. If you didn’t like what you saw and heard, kindly fuck off. This was what the Shizit was always about, but now they weren’t keeping it to themselves.

By 2002, the band publicized on their website that they wanted to add a third member to the Shizit. They found that third member in dedicated turntablist Jason Alberts. You can hear his work in the band in a few live vids circulating the net.

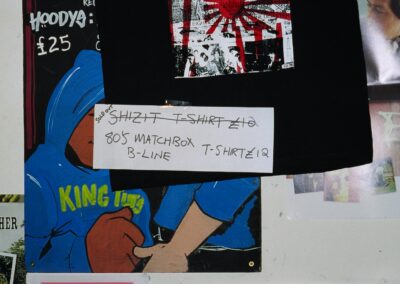

The band always knew if they were going to play live, it wouldn’t be in Seattle. It probably wouldn’t be in the United States at all. How many jungle producers do you know from the US? Do any Americans but a few of us weirdos listen to gabber and hardcore? Right. The band managed to negotiate their way as an opening act for the UK leg of Alec Empire’s tour, and what the author means by negotiate, they begged. They offered to do it for no pay and no expenses paid by the tour. They’d front it all, paperwork and all. With that kind of deal, Alec couldn’t refuse.

The band played in the UK to sold out crowds who knew them and the lyrics, but personal relations between the members fell apart during the tour. The Shizit disbanded by the end of the year.

Meditations on the End

I wish I could give you the Hollywood epilogue text, to tell you that the band remain friends today, but the reality is that they do not. Not that they hold active animosity keeping them up at night. Truthfully, I believe they simply do not think about each other or the band much anymore. They’d prefer to look forward rather than back.

I am switching to first person in this section because I want to make myself very clear. I do not care about the reason(s) The Shizit broke up. Both members have expressed regret about the ordeal, and the cliche way it all transpired. It’s best left in the past. The only conclusion I’ve ever made and ever needed is that touring is a very stressful experience for a band, especially one crossing an ocean and paying for the entire thing out of their own pockets. In those confines, people don’t so much show their true colors as they become ugly distortions of themselves. I dare you to act so high, mighty, and enlightened in the same situation. Also, you know, sometimes we all need to mind our own business more.

After The Shizit? Well, that’s the last 15 years or so. You can easily Google most of this stuff now.

JP stayed in music, releasing the first record under the name Rabbit Junk in 2004. The first record’s got a tinge of that Shizit sound, having been produced so close to the end of the other band, but it’s definitely a more personal project for him. The later records even more so. You’ll probably find it scratches some of the itch, but Rabbit Junk is not the Shizit and you’re better off not comparing them, or you’ll waste 10 years of your life getting mad over nothing like I did. Ahem. JP also has a bunch of side projects and one-offs you can look into. Before you email me, yes, I know about that one record in 2009. No, I am not wasting my time rehashing all of that. It’s good, but it’s its own thing, too.

Brian has been much more low key, quitting professional music as far as I can tell. He worked in tech for a while, seems to do a lot more traveling now, logging his destinations in a blog. He was on a podcast last year talking about what he’s been up to this whole time, like cross-continental driving (!!!), as well as little bit about the Shizit. It’s not a bad listen.

Go listen to the music. Enjoy it. These guys put a lot of work into it, and hopefully you understand that now.